3 August 2022

Causes of mortality in piglets

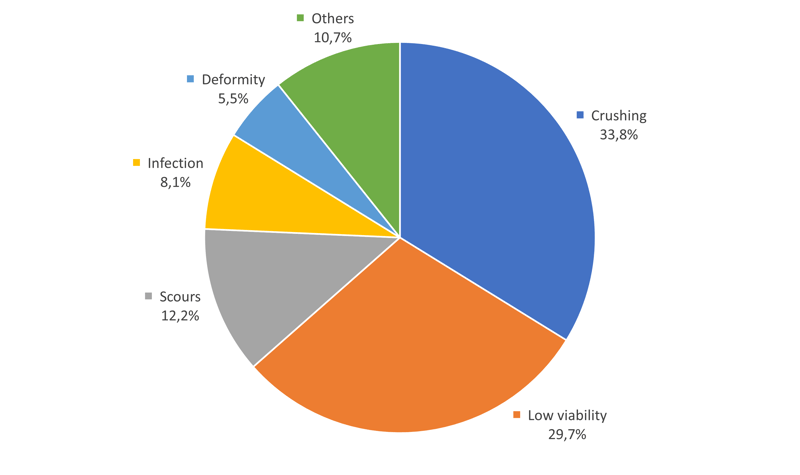

Figure 1. Causes of pre-weaning mortality from necropsy findings (adapted from Vaillancourt et al., 1990).

Figure 1. Causes of pre-weaning mortality from necropsy findings (adapted from Vaillancourt et al., 1990).

Sow crushing

By far, the most important, non-infectious cause of piglet mortality is sow crushing. Crushing occurs when the sow changes position. The most important sow behaviour that leads to crushing is rolling, followed by sit-to-lie and stand-to-lie repositioning. Crushing can also occur when a sow steps on a piglet and savaging has also been reported (Nicolaisen et al., 2019; Muns et al., 2016).

Maternal ability is an important sow factor in crushing. Because sows crush their piglets consistently over farrowing (Jarvis et al., 2005), records should be kept to inform culling and breeding decisions.

Piglet factors also influence crushing. In normal circumstances, piglets simply get out of the way of the sow. However, piglets that are failing to adapt will likely be torpid due to hypothermia, starvation, and lack of energy. Crushing is the result of a complex chain of events.

The environment also plays a role in crushing. The most obvious factor is the housing system. It is a well-established fact that farrowing crates that restrict the sows' movements significantly reduce crushing when compared to loose and group housing, and free-ranging (Hales et al., 2014). Nevertheless, sow crates have been one of the most controversial topics of debate in the pig industry. As sow welfare and ethical concerns come to the forefront, there is a push toward less restrictive housing systems. Nicolaisen et al., (2019) recently observed that most crushing deaths occur during the first 3 days post-farrowing.

Coccidiosis and scours

Within the infectious causes of pre-weaning piglet mortality, scours are by far the most significant. Piglet scours can be caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, or a combination of the three.

Rotavirus is practically ubiquitous in pig farming. However, it has low mortality. On the other hand, Transmissible Gastroenteritis (TGE) and Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea (PED) can devastate a farm. TGE can cause 100% mortality in piglets from naïve herds!

The most significant bacteria that cause scours in the farrowing unit are Escherichia coli and clostridia. E. coli, the causative agent of colibacillosis, is probably the most common cause of scour in piglets. If treated, mortality is low, otherwise, it quickly leads to dehydration and death. Clostridiasis has a very high mortality rate; however, infections usually happen when there is poor management.

Coccidia (Isospora suis) is probably the most economically significant pathogen of piglets. It causes scour and usually has low mortality. Nevertheless, it leads to significant losses throughout the production process and, because it damages the gut lining, leaves the door open for the deadly clostridia.

Coinfections are quite common. We have already mentioned how coccidia and clostridia can help each other aggravate disease. Another common pathogen association is that of viruses and E. coli.

Neonatal diarrhoeas (scours) affect piglets at different times. To assist in diagnosis, it is crucial to know the timing of the scour and also develop an eye for the characteristics of the diarrhoea. We take a deep dive into piglet scours in this article.

Passive immunity transfer failure

Because of the type of placenta that pigs have, sows cannot transfer antibodies to their piglets while they are in the womb. Therefore, piglets are born into a hostile environment… without any defences against deadly pathogens! To overcome this vulnerability, sows produce colostrum, a special ‘milk’ that is packed with antibodies and energy. During their first 24 to 48 hours of life, piglets’ guts are permeable to immunoglobulins: the antibodies they drink can pass into the bloodstream. This is called passive immunity transfer.

However, piglets’ capacity to absorb antibodies quickly declines after the first 6 hours of life! If piglets don’t drink enough colostrum as soon as possible, they will not have immunity and, most likely, will readily succumb to all and any pathogens. This is called ‘passive immunity transfer failure’.

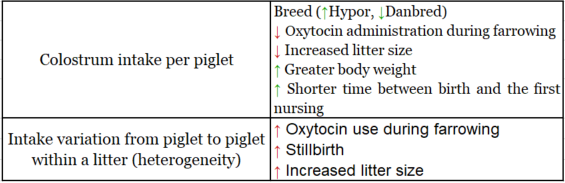

Colostrum intake depends on the ability of the sow to produce high-quality colostrum, but also on the piglets’ capacity to compete for a teat, suckle, ingest and absorb it. Declerck et al. (2017) conducted a large study to determine which factors most influence colostrum intake in individual piglets; some of the most significant are oxytocin use, large litters, and body weight within the litter. Some factors, such as stillborn piglets, also influence the variation of colostrum intake among littermates —which increases the risk of passive immunity failure for the lighter, weaker piglets.

Table 1. Factors that significantly impact colostrum intake (adapted from Declerck et al., 2017)

Table 1. Factors that significantly impact colostrum intake (adapted from Declerck et al., 2017)

Low viability

Some piglets are born underweight, weak, and have a low chance of survival if no measures are taken. In the past, there was a cut-off of around 900 g bodyweight at birth to classify underweight piglets. However, we have learned that viability is a more subtle concept, because it is also relative: an 850 g piglet might fare better around similar-sized littermates than a 1,200 g runt in a very heavy litter.

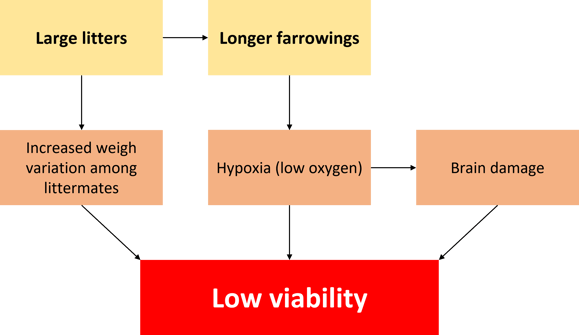

Weight at birth is not the only factor that influences viability. For example, placental infarction, umbilical cord rupture, and poor sow nutrition lead to less viable piglets. Sow prolificacy (the main genetic trait influencing litter size) has been one of the major breeding objectives in the industry. This has led to the unintended consequence of less space in the womb for all the piglets, which can cause a higher rate of unviable piglets (Tucker et al, 2021).

Dystocia, or difficulty during farrowing, can lead to asphyxia, hypoxia, brain damage, bleeding, and trauma, resulting in less viable piglets. The same could be said for longer farrowing.

Figure 2. How prolificacy leads to low viability (adapted from Tucket et al., 2021).

Another important aspect of modern pigs is that, because of their fast growth rate, they quickly outrun their iron supplies and develop anaemia, which also leads to weakness and low viability.

Low viability also puts piglets at a much greater risk of crushing.

Deformity

We should consider deformity as a subset of low viability. The most common deformity in newborn piglets is splayleg. Splay-legged piglets have low muscle tone or development so they cannot keep their legs upright. Because splaylegs cannot get away from the sow, they are very prone to death by crushing. This condition affects the hindlimbs, the forelimbs, or both (also known as ‘stars’, with an extremely low survival rate).

Most deformities, such as atresia ani (absence of anus), cardiac abnormalities, and extreme teratogenic events are fatal and result in death during the first hours or, at most, days. Others, such as hernias, could be corrected surgically, depending on the severity of the problem.

Deformities can be caused by genetic, infectious, and chemical factors (such as toxins or medicines). These problems tend to be sporadic, so, if they are becoming common on a farm, there should be a thorough investigation to determine and correct the cause.

Starvation and exposure (chilling)

Neonatal piglets prefer a temperature of 35 °C. However, this is just too hot for sows, most comfortable between 15-20 °C. Piglets with lower core temperature quickly become lethargic, so they nurse less; consequently, they have less energy to move and to keep their temperature up, leading to less activity and less willingness or ability to nurse. This is a vicious cycle that can cause death on its own or lead to crushing.

Pigs are especially susceptible to chilling because of their characteristics at birth. Their high surface-to-volume ratio means they lose heat quite fast (Tucket et al., 2021). Because they are born wet, they can quickly become hypothermic if there are drafts in the farrowing unit. Furthermore, unlike other mammals, pigs don’t have brown fat, which helps juveniles from other species maintain their body temperature, even in adverse conditions.

Agalactia

When sows fail to produce colostrum or milk, piglet mortality increases dramatically. Agalactia can result from infections, such as the Porcine Respiratory and Reproductive Syndrome (PRRS), caused by a virus.

However, agalactia is often bacterial in origin, and it rarely comes alone. Therefore, veterinarians speak of a post-partum syndrome that includes metritis (infection of the womb), mastitis (infection of the mammary glands), and dysgalactia (reduced or absent milk production). The most common term today is Post-partum Dysgalactia Syndrome (PDS), but you may also know it as lactation failure, agalactia complex, or postpartum agalactia (Kemper, 2020).

Sow malnutrition and poor body condition can also lead to agalactia.

Creating the right farrowing environment

As we have seen so far, the causes of piglet mortality are many and they interact in complex ways. Therefore, focusing all your energy on just one apparent cause is usually not the best long-term strategy. The best way to reduce piglet mortality rate is to create the right farrowing environment. Favourable conditions will eliminate most of the specific causes and, should a problem arise, it will be easy to detect and root out.

The first step to create a good farrowing environment is to keep an open mind and not overlook the obvious. A simple walk around the farm, with a critical eye, will reveal the major areas of opportunity: do we have a drafty farrowing pen? Are there rodents or other vermin present on the premises? Did we formulate a diet for the sows? Are the farrowing crates clean?

Spending a few minutes drawing a diagram of the complete production process is also a useful exercise. This will reveal some of the most impactful mistakes: are we mixing age groups? Are we skipping the gilt quarantine period? Are we skipping the gilt acclimation period? Are we weaning too early or too late? Are we cross-fostering too much or not enough?

The next step is to create a checklist for the farrowing unit. Even though it is an integral part of the farm, the farrowing unit should be managed as an almost separate entity. Because even small mistakes during farrowing will have a big impact on herd productivity, it is important to have a farm policy and to have a systematic approach to management.

We have created a guide that will take you step by step in the creation of a checklist for your farrowing area, from gilt selection all the way to stockmanship.

How to reduce piglet mortality in the farrowing unit

We now take a look at the specific measures to reduce piglet mortality. Because of the nature of pre-weaning deaths, each of these techniques will address several causes at once. Nevertheless, keep in mind that investing in just one area is likely to have a lower positive impact than if you took steps to address the general environment in your farrowing unit.

Sow crushing prevention measures

In industrial farming, the solution to pig crushing has been the restraining of the sow in a crate. Some farrowing crates allow greater movement than others. Crating is a controversial topic of discussion in the pig industry because there are many welfare and ethical concerns. Farmers often have to weigh sow welfare against the risk of crushing and piglet welfare. Loose and group housing solutions have been proposed, but these have greater rates of crushing than crating.

Most farrowing pens have a safe area the sow cannot access, together with a heated creep area. This solution increases piglet survival because it also prevents chilling. However, creep area acceptance is not very high. Nicolaisen et al. (2019) studied sow and piglet behaviour in three different types of farrowing pens: crate, loose, and group housing. They observed that pen design significantly influences how piglets behave. In the first days of life, piglets like to stay close to their dam and their littermates. The greater the distance between the sow and the creep area, the higher the probability that the piglets will not go inside it; therefore, they will tend to rest closer to the sow, increasing the risk of crushing.

These researchers from Hannover University also confirmed some interesting points about sow behaviour post-farrowing. Due to exhaustion, sows lie in a resting position 90% of the time during the first 3 days post-partum! As we know, in free life, sows have a very strong nesting behaviour and they practically stay in the same place in the days that follow farrowing. Nicolaisen and his co-authors propose this could be an evolutionary mechanism to prevent crushing. This could be, but the implication is that piglet behaviour has a greater impact on the risk of crushing than sow behaviour.

Therefore, designing the farrowing pen so that the sow can lie close to the creep area is a major factor that can reduce crushing. Another aspect of pen design that has been widely adopted is anti-crushing bars. These prevent the piglet from getting caught between the sow and the wall.

As they grow, piglets more readily accept the creep area

and the risk of crushing (as well as the need to restrain the sow) diminishes.

These are the specific measures to reduce sow crushing:

- Design farrowing pens to allow the sow to lie close to the creep area.

- If you restrain the sow, do so during the first 3 days post farrowing (most crushing events occur during this period).

- Don’t allow piglets to rest in the cold areas next to the sow (use split suckling, which will also reduce crushing due to chilling and starvation).

- Include anti-crushing bars in your farrowing pen design.

- Don’t select replacement gilts from dams with a history of crushing.

- Cross-foster piglets within 48 h post-farrowing.

Prevent Septicaemia in Pigs

Septicaemia is a scientific term for ‘blood poisoning.’ When bacteria infect a piglet, they can ‘poison the blood’ through toxins and even bacteria themselves entering the bloodstream (bacteraemia). As the bacteria spread, they elicit a very aggressive inflammatory response. Septicaemic piglets become feverish, lethargic, stop nursing, and will soon die from the infection, that is if they are not crushed in the process.

The main cause of septicaemia in pigs is poor immunity, most likely due to a lack of colostrum. Another important source of septicaemia in piglets is E. coli, which is also a frequent cause of scouring.

These are the most important measures you can take to prevent septicaemic diseases in the farrowing unit:

- Ensure that piglets get enough colostrum.

- Vaccinate sows pre-farrowing.

- Increase farrowing unit hygiene and biosecurity.

- Use prophylaxis where appropriate (for example, against coccidia).

Manage colostrum

The importance of colostrum cannot be overstated!

By far the most common reason why piglets don’t get enough colostrum is that they are born to a large litter. Since this is also one of the main factors influencing low viability, the effect is compounded. Therefore, litter equalisation through cross-fostering is widely practised in modern pig farming.

There are several cross-fostering techniques . As a general rule, it should not be overdone, and it should be accomplished during the first 48 hours post-farrowing. Everything should be done to promote that cross-fostered piglets receive at least one stomach full of colostrum from their biological dam. To accomplish this, split suckling is very useful.

Litter equalisation has its pros and cons. However, it is a fact that it reduces neonatal mortality in lower-weight piglets.

The main colostrum management techniques are split suckling, teat training, and bottle feeding. Split suckling consists in using a box to keep part of the litter inside the creep area, allowing the rest of the piglets free access to the sow. Split suckling is cheap, convenient, and very effective because it also reduces chilling, forcing piglets to spend some time in the heated creep area. Split suckling can be seamlessly integrated into the farrowing pen workflow.

Teat training should be done selectively, with the smaller littermates. It consists in manually approaching the piglet to a teat and encouraging it to drink. Teat training (also called assisted nursing/suckling) ensures that the most vulnerable piglets ingest colostrum, decreasing overall mortality.

Finally, bottle feeding consists in manually feeding a piglet. This can be accomplished with a bottle or with a nasogastric tube. Colostrum can be extracted from the dam or, if this is not possible, from another sow, that has farrowed recently. Some advocate keeping frozen colostrum on site; while this is certain to reduce mortality, we should question its cost-effectiveness.

| Technique | Labour-effectiveness | Time-effectiveness | Cost-effectiveness |

| Split suckling | High | High | High |

| Teat training | Medium | Medium | High |

| Assisted feeding | Low | Low | Dubious |

Table 2. Colostrum management techniques.

This is a short list summarizing the most effective measures to reduce pig mortality due to passive immunity transfer failure:

- Decrease oxytocin use during farrowing (Declerck et al., 2017).

- Have a clear cross-fostering policy and train farrowing unit personnel.

- Equalise litters within 48 h post-farrowing.

- Encourage piglets to nurse, if possible, within the first hours after farrowing.

- Use split suckling as a matter of policy in all litters larger than 12 piglets.

- Train farrowing unit personnel in advanced assisted feeding techniques (teat training, assisted feeding).

- Implement batch farrowing to facilitate cross-fostering.

Increase biosecurity

Having a clear biosecurity policy on the farm will allow you to quickly detect potential threats. In general, biosecurity will decrease piglet mortality by reducing the overall circulating pathogens. Agalactia will also decrease in sows, which will also positively impact piglet survival.

The best advice when it comes to biosecurity is to keep it simple, keep it visible, and keep personnel in the know.

- Keep it simple: if personnel need to go out of their way to comply with biosecurity, they will find loopholes in the system and create vulnerabilities. For example, if changes of clothes are kept under lock, workers will move between areas without changing.

- Keep it visible: clean areas should be clearly marked and personnel should be able to know it at a glance. For example, having colour-coded clothing for each area with matching walls is an effective way to detect when someone or something is in the wrong place.

- Keep personnel in the know: a masterfully written biosecurity protocol that stays in the office drawer is useless. Workers, especially those in the farrowing unit, should be aware of biosecurity policies. To keep them motivated, recruit a biosecurity champion from within their ranks.

Learn more about biosecurity in the pig farm and how to add it to your workflow.

Batch farrowing

Batch farrowing, a technique that became popular in the ‘70s, has made a comeback. Essentially, it consists in synchronising groups (or batches) of gilts and sows so that they farrow close to each other. The next batch is synchronised for several weeks after and so on.

The key behind batch farrowing is that it allows smaller farms to have an all-in/all-out approach. Batch farrowing benefits workers in many ways. They can focus on the farrowing area during the intensive farrowing periods, with weeks where the workload is lower, allowing for more routine variation, vacation planning, and a more satisfying work experience. The benefits of batch farrowing for biosecurity are immense because the farrowing pens can be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected between batches. There are additional cost benefits down the production line, especially in transport. Litter equalisation is also easier with batch farrowing and there is less of a temptation to mix groups.

The main pitfall of batch farrowing is when there are bottlenecks in the grower and finisher areas. Curious as it sounds, overfarrowing can be a serious problem in modern pig farming!

Batch farrowing decreases piglet mortality because of its biosecurity benefits, a more motivated and focused workforce, and the ease of litter equalisation.

Iron supplementation

As we have mentioned previously, modern piglets have a very fast growth rate. This means that they run out of their iron reserves quickly and can become anaemic. These piglets will have lower energy, suckle less frequently, and risk being crushed by their dam.

Usually, iron supplementation was given after day 3, for fears of injection injuries. Fortunately, pig farmers can count on top-quality products, which allow them to safely and effectively supplement iron to their piglets from day 1.

Stockmanship and farrowing unit management

Even as technology advances and all sorts of contrivances appear on the market to reduce piglet mortality, farmers and their workers remain a vital element to successful pig production.

Stockmanship is crucial well before farrowing. Handling sows is no easy task and it takes experience to do it safely and without stressing the animals. Good handling in the farrowing area starts when the sows are moved to the farrowing unit.

During farrowing, good workers know when to assist a sow, keep oxytocin use to a minimum, and take the initiative to promote colostrum intake; they dutifully dry newly born piglets and feel they have a personal stake in the success of their litters. Record keeping and good communication skills are also important. Workers with a keen eye are the first to notice when something is wrong.

After farrowing, there are many tasks to accomplish: teeth clipping, tail docking, iron supplementation, coccidiosis prophylaxis, and, depending on local legislation, even castration. Carelessness while performing these tasks increases piglet mortality. Even something so simple as giving an injection can result in a dead piglet when done incorrectly. For this reason, all farrowing area personnel should receive training and continuous education.

Learn more about farrowing unit management.

References

Alarcón, L. V., Allepuz, A., & Mateu, E. (2021). Biosecurity in pig farms: a review. Porcine Health Management, 7(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40813-020-00181-z

Declerck, I., Sarrazin, S., Dewulf, J., & Maes, D. (2017). Sow and piglet factors determining variation of colostrum intake between and within litters. Animal, 11(8), 1336-1343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731117000131

Hales, J., Moustsen, V. A., Nielsen, M. B., & Hansen, C. F. (2014). Higher preweaning mortality in free farrowing pens compared with farrowing crates in three commercial pig farms. Animal, 8(1), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731113001869

Jarvis, S., D'Eath, R. B., & Fujita, K. (2005). Consistency of piglet crushing by sows. Animal welfare, 14(1), 43-51. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ufaw/aw/2005/00000014/00000001/art00006

Kemper, N. (2020). Update on postpartum dysgalactia syndrome in sows. Journal of animal science, 98(Supplement_1), S117-S125. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skaa135

Kim, S. W., Weaver, A. C., Shen, Y. B., & Zhao, Y. (2013). Improving efficiency of sow productivity: nutrition and health. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 4(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-1891-4-26

Mullan, B. P., Davies, G. T., & Cutler, R. S. (1994). Simulation of the Economic Impact of Transmissible Gastroenteritis on Commercial Pig Production in Australia. Australian Veterinary Journal, 71(5), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1994.tb03370.x

Muns, R., Nuntapaitoon, M., & Tummaruk, P. (2016). Non-infectious causes of pre-weaning mortality in piglets. Livestock Science, 184, 46-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2015.11.025

Nicolaisen, T., Lühken, E., Volkmann, N., Rohn, K., Kemper, N., & Fels, M. (2019). The effect of sows’ and piglets’ behaviour on piglet crushing patterns in two different farrowing pen systems. Animals, 9(8), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9080538

Ocepek, M., & Andersen, I. L. (2017). What makes a good mother? Maternal behavioural traits important for piglet survival. Applied animal behaviour science, 193, 29-36.

Ozsvary, L. (2018) Production Impact of Parasitisms and Coccidiosis in Swine. Journal of Dairy, Veterinary & Animal Research, 7(5), 217-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.15406/jdvar.2018.07.00214

Pensaert, M. B., & Martelli, P. (2016). Porcine epidemic diarrhea: a retrospect from Europe and matters of debate. Virus research, 226, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.030

Tucker, B. S., Craig, J. R., Morrison, R. S., Smits, R. J., & Kirkwood, R. N. (2021). Piglet Viability: A Review of Identification and Pre-Weaning Management Strategies. Animals, 11(10), 2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11102902

Vaillancourt, J. P., Stein, T. E., Marsh, W. E., Leman, A. D., & Dial, G. D. (1990). Validation of producer-recorded causes of preweaning mortality in swine. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 10(1-2), 119-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0720(15)30711-8

Vande Pol, K. D., Tolosa, A. F., Shull, C. M., Brown, C. B., Alencar, S. A., Lents, C. A., & Ellis, M. (2021). Effect of drying and/or warming piglets at birth under warm farrowing room temperatures on piglet rectal temperature over the first 24 h after birth. Translational Animal Science, 5(3), txab060. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txab060

Vidal, A., Martín-Valls, G. E., Tello, M., Mateu, E., Martín, M., & Darwich, L. (2019). Prevalence of enteric pathogens in diarrheic and non-diarrheic samples from pig farms with neonatal diarrhea in the North East of Spain. Veterinary Microbiology, 237, 108419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108419