5 July 2022

Causes of diarrhoea in neonatal piglets

Neonatal diarrhoea in piglets is one of the leading causes of disease and mortality in the farrowing unit. Even when piglets survive, the consequences to pig development and performance can seriously damage the farm’s finances and profits.

Diarrhoea (or scour) can have several causes, not all of them infectious. There is not a single approach to manage and prevent it. Problems with stockmanship, biosecurity, or nutrition, soon manifest as piglet diarrhoea. It is only natural to want a straightforward explanation whenever there is an outbreak, however, this simplistic way of looking at a very complex picture often means that efforts to manage the disease are unsuccessful. Neonatal scour should always be considered a multi-causal phenomenon.

There are four pillars that favour the appearance of diarrhoea in the farrowing unit:

- Poor immunity

- Poor environment

- Poor stockmanship

- Pathogens

These pillars work in tandem. For example, suppose a careless farrowing unit worker fails to ensure that smaller piglets drink colostrum; they will be susceptible to a host of pathogens, which also benefit from a dirty environment. In our example, as piglets begin to scour, the litter is given antibiotics indiscriminately, which damages their gut microbiome, making them even more prone to diarrhoea. Soon, cases start to mount and, even if not many piglets die, the impact will be felt most acutely in the profits. It is easy to see how poor management lies at the root of neonatal diarrhoea.

As pig farming intensifies, there is less room for error, so even in exceptionally well-managed farms there are occasional outbreaks. This is due in part to the exceptional resilience of some pathogens, such as coccidia, which are nearly impossible to eradicate from herds.

Poor immunity as a contributing cause of neonatal diarrhoea

The placenta prevents piglets from getting antibodies from their dam when they are in the womb. They can’t create their own defences either because they live in a practically sterile environment. Then, at farrowing, they are thrown defenceless into a hostile milieu. Thankfully, sow colostrum is packed with antibodies and piglets’ gut can "absorb" these life-saving defences. This is called "passive immunity transfer". It is passive because the piglet did not have to synthesise antibodies on its own (active immunity).

When piglets do not get enough colostrum, they are easy prey to any microorganism that is present in the environment. This means that not only dangerous bacteria and viruses can harm the newly farrowed piglet, but any microorganism, even beneficial ones, can quickly get out of hand. This is why piglets that do not drink colostrum die so quickly and why treatment with antibiotics is futile in these cases.

The window of opportunity closes quickly because antibody concentration drops quickly in milk and the piglet’s gut becomes impermeable to maternal antibodies, the piglet is no longer receptive to the sow’s immunity. Normally, the passive immunity transfer window closes at 48 hours at the latest. However, a well-managed farrowing unit makes it a top priority to ensure that all piglets get enough colostrum.

There are some other factors that can cause poor passive immunity transfer. Agalactia (when sows don’t produce milk) is a serious concern. Large litters, poor gilt selection (poor maternal abilities, too few or poor-quality teats, etc.), and an unfavourable environment can contribute to some piglets not getting colostrum. Stockmanship is crucial to increase the success of passive immunity transfer.

When the sows have not been exposed to certain pathogens, they will not have circulating antibodies against these diseases, so they will not be able to confer protection to their piglets, even if they drink enough colostrum. The consequence is that piglets simply will not be immune. This happens, for example, when replacement gilts are not correctly acclimated to the herd or vaccinated.

Sow selection has focused on prolificacy in the last decades, leading to very big litters that often surpass the dam’s ability to provide colostrum, milk, and iron to all its piglets.

Poor environment as a contributing cause of neonatal diarrhoea

Picture the following scenario: a litter is born to a top-performing sow, perfectly healthy, and drinks enough colostrum, but the farrowing pen is dirty, damp, drafty, and cold, without any additional heat source. To make matters worse, the sow is getting a poor-quality diet and is developing a shoulder sore that goes unnoticed. One would expect this litter to deteriorate quickly, and, in fact, it is only a matter of days before piglets start scouring and dying.

The environment affects farrowing unit performance in several ways. A poor environment causes stress in the sow, which can lead to less milk production, diminished appetite and, in the long run, more days to the next farrowing. If the sow is being affected, the piglets will have fewer resources to fend off disease and, sooner or later, they will begin to scour.

In a poor environment, piglets themselves will use their precious resources to simply stay alive.

Finally, a dirty environment provides many opportunities for pathogens to hide and, even with the best-quality colostrum available, sometimes the sheer amount of viruses and bacteria is so great (high pathogen burden) that diarrhoea becomes inevitable.

Bedding is a common source of contamination so it is shunned in most intensified systems. However, in more traditional farms it is very comfortable for piglets. Dirty bedding should be removed daily from the farrowing pen and replaced completely between litters.

Poor management as a contributing cause of neonatal diarrhoea

In modern pig farming, stockmanship and management remain crucial factors in the farrowing area. Good personnel work tirelessly to enforce biosecurity rules and therefore reduce the pathogen burden in the environment. They also take care of their piglets with an eye for cross-fostering and ensure that piglets get all the colostrum they need. Good workers also notice when something goes wrong, so they can limit outbreaks and reduce mortality.

Pathogens that cause diarrhoea in neonatal piglets

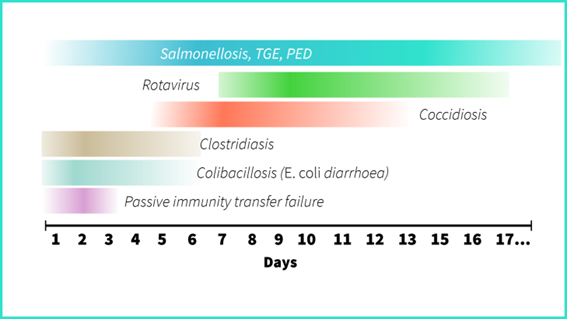

There are many bacteria, viruses, and protozoans (one-celled parasites) than can cause neonatal diarrhoea in piglets. Some, such as coccidia, are practically ubiquitous, whereas others are more specific to certain regions or production systems, such as Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea (PED). You should also keep in mind that some types of scour are more common at certain stages of the process. These are the most important in the farrowing unit:

Rotavirus, Transmissible Gastroenteritis (TGE), and PED

Viral diarrhoeas in piglets are characterised by a watery scour that lasts for a few days. Piglets can become dehydrated quickly. Coinfections with bacteria (such as Escherichia coli) are common and can dramatically increase the mortality of an outbreak. There is no treatment for viral infections, so veterinarians will treat the dehydration and coinfections as they appear.

Rotavirus is practically ubiquitous and very difficult to eradicate from a farm because of the virus’ triple-layer capsid, which makes it impervious to practically all disinfectants. TGE and PED are both caused by coronaviruses. TGE is devastating for piglets in naïve herds and can cause up to 100% mortality! Nevertheless, as the TGE becomes endemic on a farm, it becomes a self-limiting disease. PED is similar to TGE, but not as aggressive.

Coccidiosis

Coccidia (Cystoisospora suis) are probably the most economically significant parasites of pigs. These unicellular parasites invade the gut lining where they reproduce at a vertiginous rate, damaging the gut’s absorptive capacities. It is normally not deadly to pigs but it carries huge consequences for performance all throughout the production process. Subclinical infections (pigs without signs) are quite problematic for farms, because these individuals keep shedding oocysts (coccidia ‘eggs’) and contaminating the environment.

Coccidiosis diarrhoea is usually creamy, but it can progress to a more watery scour when other pathogens are involved. Treating coccidiosis is not very effective and not economically prudent. Therefore, the best strategy is to prevent piglets from getting the disease in the first place. There is a class of drugs known as coccidiostats that can be used for metaphylaxis on positive farms.

Clostridiosis

Clostridia are deadly bacteria that cause some of the most aggressive scours. Paradoxically, they are normal inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract. Clostridia are also incredibly difficult to eliminate from the environment because they can form spores diminutive ‘seeds’ that are among the hardiest biological structures known to science.

Clostridiosis usually occurs when there is an imbalance in the gut that allows Clostridia to thrive. For example, when antibiotics are used indiscriminately, many beneficial bacteria that keep clostridial species in check die; soon thereafter, the population of clostridia explodes. When other pathogens, such as Coccidia, damage the gut lining, this creates the perfect environment for these bacteria. Finally, gorging can also favour clostridiosis; in fact, one of the telltale signs of the disease is that it is usually the biggest, fattest piglets that die first.

Between the most important Clostridia that cause diarrhoea in neonatal piglets: Clostridium perfringens type C (CpC), and C. perfringens type A (CpA), CpC is the most aggressive and causes haemorrhagic diarrhoea; piglets can die so quickly that they might not even have time to scour. CpA causes a pasty diarrhoea and is not as deadly. CpA is one of the most frequently diagnosed bacterial pathogen causing ND nowadays.

Escherichia coli diarrhoea

Colibacillosis is one of the most common scours of neonatal piglets. It is characterised by a profuse, watery diarrhoea that can dehydrate pigs quickly and cause them to die. E. coli comes in many varieties. Some are normal inhabitants of the gut. However, toxigenic strains can wreak havoc in the farrowing area. In fact, another name for colibacillosis is neonatal diarrhoea: it is the most typical of all piglet scours.

E. coli usually affects very young piglets but, when there are viral infections, older pigs can develop secondary colibacillosis.

Salmonellosis

This bacterial disease is most often associated with older pigs during the weaner and growing stages. However, it is also of concern to the farrowing area. The bacteria that cause salmonellosis in pigs are Salmonella enterica serovars Cholerasuis and Typhimurium. S. Cholerasuis is deadlier but it is often a problem later in life. S. Typhimurium is more common in piglets, though it has low mortality.

Salmonellosis should never be underestimated. First, pigs can shed bacteria in their faeces months after they recover, so it is easy to see how the disease can be introduced to the farrowing area. Second, salmonellosis is a zoonosis: it can affect humans too.

Other infectious diseases to keep in mind

A very interesting disease we should consider is the porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome (PRRS). This viral disease does not cause diarrhoea in piglets by itself, but because it does produce agalactia in sows, it leads to scouring because of a failure of passive immunity transfer. Because it can infect piglets even before they are born, it is also an important cause of stillbirths and neonatal mortality.

Scouring: Factors to consider when diagnosing neonatal diarrhoea

Piglet neonatal diarrhoea is a multicausal, complex disease. As we have discussed in the previous section, there are many factors that, together, can create a very difficult situation to untangle. Diagnosing piglet scour is very complicated!

To determine what is the main cause of neonatal diarrhoea on a farm, veterinarians must act as detectives. These are some of the criteria they use to weed out the culprit:

Timing of scour

Scours appear at different times depending on the pathogen or the primary cause. For example, coccidiosis usually appears on day 7 and never earlier than day 5. Clostridiosis appears early, as well as colibacillosis. However, the earliest scour is usually not due to any specific pathogen: it is a lack of colostrum.

Viral infections are usually second-week scours. However, this does not really apply to TGE in naïve herds; the disease spreads incredibly fast even in very young piglets because of its short incubation period (as short as 18 hours).

Timing is an important clue, but it should not be used by itself to diagnose neonatal diarrhoeas. In conjunction with other criteria, it allows veterinarians to decide which diagnostic tests to order and what emergency measures to take to prevent further damage.

| When did the diarrhoea appear? | Most probable causes |

| First 3 days | Passive immunity transfer failure (agalactia, piglets did not drink colostrum, poor quality colostrum). |

| First 5 days | Clostridiosis (pasty scour), colibacillosis (watery scour). |

| Days 7 to 10 | Coccidiosis |

| Days 7 to 15 | Rotavirus. |

| Any time | Salmonellosis, TGE, PED |

Type of scour

Each pathogen causes diarrhoea by a different mechanism. For example, E. coli has toxins in its cell membrane that ‘trick’ the gut cells into secreting a lot of water, so the result is a profuse, watery diarrhoea. C. perfringens type A secretes a toxins: Alpha and Beta 2 toxins, that destroys the gut lining , so the result is a different grade of the diarrhoea. Coccidia thin out the gut lining, so it cannot absorb food, resulting in a scour with varied consistency.

When trying to narrow out the causative agent by type of diarrhoea, look at colour, consistency, and smell for clues. However, you should never base your diagnosis on these signs alone.

| Cause of scour | Colour | Consistency |

| Rotavirus | Clear to yellow | Watery |

| TGE and PED | Yellow to green | Watery |

| Clostridiosis | Yellow to black | Pasty (can be watery with C. difficile) |

| Colibacillosis | Clear to yellow | Watery |

| Coccidiosis | Yellow to grey | Pasty |

| Salmonellosis | Yellow to green (can have blood specks) | Watery |

Necropsy findings and laboratory tests

Some piglet scours have very characteristic gross signs that veterinarians can identify with a high degree of certainty (sometimes called "pathognomonic"). For example, the brain-like texture of PPE gives the disease away. Clostridiases are often easy to diagnose because of the bloody gut they leave behind. Other diseases are much more subtle and it is hard to give even a tentative diagnosis.

When sending samples to the lab, it is important to have a clear idea of what are the most probable causes. For the fast diagnostics of ND (Neonatal Diarrhoea) on the farm, the Point-of-care (POC) tests might be considered and used. Tests offer a wide range of benefits regarding disease prevention, early detection, and fast decision together with following confirmation and characterizing of pathogen in the laboratory.

Here is a table with the preferred samples and tests for each of the diseases we have been discussing:

| Cause of scour | Preferred samples | Preferred tests |

| Rotavirus, TGE, and PED | 1. Diarrhoeic faeces | 1. ELISA, PCR |

| 2. Small intestine | 2. Histology, immunohistochemistry | |

| 3. Point of Care (POC) on farm | ||

| Clostridiosis | 1. Intestine | 1. Histology |

| 2. Gut contents or swab | 2. Culture | |

| 3. POC on farm | ||

| Colibacillosis | 1. Gut contents | 1. Culture and PCR |

| 2. POC on farm | ||

| Coccidiosis | 1. Faeces 2 to 3 days after scour appears and in series | 1. Parasitology- flotation, autofluorescence and PCR |

| Salmonellosis | 1. Gut contents or intestine sections | 1. Culture |

| 2. Blood | 2. ELISA |

Vaccination against neonatal diarrhoea

Unless there is a failure of passive immunity transfer, piglets are usually protected from some of the pathogens that cause neonatal diarrhoea thanks to the colostrum. When investigating an outbreak, the first thing to rule out is whether piglets got enough colostrum… if they didn’t, that is the most likely cause!

Once passive immunity transfer failure has been ruled out, the vaccination program should be analysed. Together with other diagnostic criteria, veterinarians can obtain valuable clues from looking at what vaccines the sows got.

| Cause of scour | Vaccination recommendations |

| Rotavirus A | Vaccinate in late gestation. |

| TGE and PED | Vaccinate sows. |

| Clostridiosis (A and C) | Vaccinate sows. |

| Colibacillosis | Vaccinate gilts and sows in late gestation. |

| Coccidiosis | Currently, there are no vaccines available. |

| Salmonellosis | General vaccination. |

Coccidia control program

Because they are practically ubiquitous, controlling coccidia is a necessary feature of modern pig farming. If the answer to the question: "what are we doing to control coccidiosis?" is "nothing", then it is a likely culprit of neonatal diarrhoea.

Coccidiostats should be given prophylactically. Oral coccidiostats seem an economical and easy way to prevent and control coccidiosis. However, the oral route leads to many piglets getting a suboptimal dosage, especially those that need it the most. Injected coccidiostats guarantee accurate dosages and that every piglet gets the prophylaxis it needs. It is simply the best practice for the farrowing area!

When investigating a neonatal diarrhoea outbreak, it is paramount to review the coccidia control program.

Biosecurity protocols

Whenever there is a diarrhoea outbreak, veterinarians should investigate if there is a biosecurity protocol in place and if it is adequate to the farm’s needs. Performing a "biosecurity audit" reveals whether the protocols in place are actually enforced. If there is no system for accountability, chances are there are biosecurity leaks. Some pathogens, especially coccidia, are incredibly resilient in the environment and pests (mice, pigeons, insects) can play a role in its transmission. Whenever there is an outbreak that cannot be explained from within the farrowing unit, the investigation should extend well beyond the farrowing area.

Piglet care and management to minimise scouring

The intense planning and labour that goes into the farrowing area all aim at providing piglets the best conditions for survival and development. For an extensive discussion and many valuable tips, visit our Farrowing Area Checklist page.

To minimise neonatal diarrhoea in the farrowing unit, these are the main strategies:

Colostrum management

The importance of colostrum in piglet management cannot be overstated. As we have discussed above, piglets that do not get enough quality colostrum will most likely scour and die. Furthermore, remember that there is a window of opportunity that closes quickly. After the first 48 hours of life, if piglets did not suckle enough colostrum, their probabilities of survival are greatly reduced.

The main reasons why piglets fail to drink colostrum on their own are:

- Big litters where smaller or weaker piglets have to compete with more precocious littermates for a limited number of teats.

- The sow does not have enough functional teats.

- The teats have poor conformation, so some piglets have trouble nursing.

- Some piglets in the litter are just too weak to nurse.

There are two main strategies to help piglets. Split-suckling, or separating part of the litter for 60-90 minute periods, allows smaller piglets to nurse without having to compete with littermates. Some piglets have trouble latching to the teat, so training them to nurse is a good strategy, though it is time-consuming; for this reason, it should be done selectively with the smaller piglets in a litter, and during the first half hour of life.

There are more advanced techniques, such as bottle feeding. However, this is too time and labour consuming, so it is not practical for most farms.

Cross-fostering

Cross-fostering is a controversial topic. Its main function is to equalise litters, so that there are enough teats available and also to create litters more homogenous in piglet weight. Cross-fostering should be done early, but only after piglets have received enough colostrum from their dam. In the case of orphan piglets, it is possible to foster them with a nursing sow.

There are several techniques, but every farrowing area should stipulate clear cross-fostering policies.

Biosecurity

Cleaning and disinfecting the farrowing unit is paramount to minimise neonatal diarrhoea. Some pathogens, such as rotavirus and coccidia are very hard to eliminate. Nevertheless, thorough cleaning can reduce the pathogen burden.

All-in/all-out management and batch farrowing are techniques that can be considered as a part of a comprehensive biosecurity program. Whichever actions you decide to undertake, a clear biosecurity policy that is communicated to all personnel is an integral part of the farrowing area.

Coccidiosis control and iron supplementation

Normally, coccidiostats are injected around day 3. Nevertheless, the best products can be administered much earlier. As discussed previously, all farms should consider coccidiosis mataphylaxis because the disease is ubiquitous and practically impossible to eradicate from a farm.

Modern piglets have a peculiarity. Because they have been selected to grow as fast as possible, they quickly outgrow the iron supplies that they receive from their dams, and what they can get from the milk is simply not enough. Iron-deficient piglets develop anaemia. Because these pigs quickly become weak and stop feeding, they become prey to all sorts of pathogens and can suffer secondary scour. Supplementing iron to piglets in their first days of life should form part of any piglet management program.

References

Alarcón, L. V., Allepuz, A., & Mateu, E. (2021). Biosecurity in pig farms: a review. Porcine Health Management, 7(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40813-020-00181-z

Hales, J., Moustsen, V. A., Nielsen, M. B., & Hansen, C. F. (2014). Higher preweaning mortality in free farrowing pens compared with farrowing crates in three commercial pig farms. Animal, 8(1), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731113001869

Kim, S. W., Weaver, A. C., Shen, Y. B., & Zhao, Y. (2013). Improving efficiency of sow productivity: nutrition and health. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 4(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-1891-4-26

Mullan, B. P., Davies, G. T., & Cutler, R. S. (1994). Simulation of the Economic Impact of Transmissible Gastroenteritis on Commercial Pig Production in Australia. Australian Veterinary Journal, 71(5), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1994.tb03370.x

Ocepek, M., & Andersen, I. L. (2017). What makes a good mother? Maternal behavioural traits important for piglet survival. Applied animal behaviour science, 193, 29-36.

Ozsvary, L. (2018) Production Impact of Parasitisms and Coccidiosis in Swine. Journal of Dairy, Veterinary & Animal Research, 7(5), 217-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.15406/jdvar.2018.07.00214

Pensaert, M. B., & Martelli, P. (2016). Porcine epidemic diarrhea: a retrospect from Europe and matters of debate. Virus research, 226, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.030

Vande Pol, K. D., Tolosa, A. F., Shull, C. M., Brown, C. B., Alencar, S. A., Lents, C. A., & Ellis, M. (2021). Effect of drying and/or warming piglets at birth under warm farrowing room temperatures on piglet rectal temperature over the first 24 h after birth. Translational Animal Science, 5(3), txab060. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txab060

Vidal, A., Martín-Valls, G. E., Tello, M., Mateu, E., Martín, M., & Darwich, L. (2019). Prevalence of enteric pathogens in diarrheic and non-diarrheic samples from pig farms with neonatal diarrhea in the North East of Spain. Veterinary Microbiology, 237, 108419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108419